The evolution of IT security in recent years has generated a wide range of sensations: sometimes we feel like we are tripping over the same stone over and over. Other times, it’s more like a déjà vu. And sometimes it even feels like we’ve reencountered Punxsutawney Phil, the groundhog.

For a long time, we’ve invested considerable resources in protecting intelligence and trying to stay one step ahead of cyber threats through information management, while still monitoring the desktop. We can add all the adjectives we want – artificial intelligence or big data – but in the end the goal is the same. We also try to shape the behaviour of our users or detect anomalies in our organisation. We’ve seen these strategies before and they seem to come back cyclically, bolstered with new technologies.

But despite everything, we continue to have the same problem: we are still seeing information leaks, sabotage, blackmail, cyber espionage and other types of threats to computer security. While it is hard for some security software manufacturers or IT security companies to admit it, 100% security is simply impossible. The only thing we can do is implement a strategy for minimizing risk, and when a security incident does happen, be ready to respond efficiently and sensibly.

People are the weak variable in the equation. Human error is increasingly the cause of security incidents: opening a file, entering our credentials in a phishing site, keeping our passwords in a text file, sharing our confidential information in public tools, connecting to a wireless network without taking precautions, checking the company email from a hotel computer while on a holiday, etc. The list of human errors is endless.

The fact is that most incidents are not all that sophisticated; most are not EternalBlue or any of the other exploits being used by criminal groups, companies or even governments. We are more likely to see stolen credentials, a few lateral movements using system tools and creating a backdoor for data exfiltration using connections to totally legitimate websites.

Cybersecurity incidents will never disappear. Our mission is to try to reduce the number of incidents and manage them correctly.

Attackers vs. defenders

We’ve often heard that there is a great asymmetry in the relationship between attackers and defenders: in order to compromise our security, the attacker needs only to find a small gap, while as defenders we have to control a wide swath of terrain. While this asymmetry does in fact exist, the defensive teams are often not doing everything we can to defend ourselves.

The blue team (defensive) traditionally concentrates all our efforts on automated products or services, thinking that for the investment we make these products should be able to protect us from all threats, both known and unknown. The red team (offensive), on the other hand, also has automated products or services, but also counts on several secret ingredients: an arsenal of small tools, sideways thinking, and even clever that spring to mind spontaneously during a cyber attack. Why don’t the people on the blue team have this attitude?

One step further

It’s not only a change in mentality that we need; we must substantially raise the level of difficulty and repercussions for the attacker when targeted.

We’ve seen this coming for nearly 10 years. Many of the security incidents are targeted and persistent, which means that even if we find the gap breached by our adversaries, by the time we fix the problem they’re bound to have found several more. They are directly interested in us, and not because they’ve randomly ended up in our networks. It’s something we must assume, and therefore internalise in our strategy.

Capabilities and objectives will vary depending on the type of adversary (employees, subcontractors, competitors, criminals or even nations), but their efforts are marked by their persistence.

The United States Congress is trying to pass a regulation that will allow private companies to do more. Unfortunately, most of the proposals fall by the wayside because many of them support the practice of ‘hacking back’.

The business of hacking back is way off the mark. The collateral effects can be unexpected and unpredictable. It is something that most of us are completely against, even though the practice is used in certain environments.

The most recent proposals presented to the US Congress are beginning to make more sense: they now focus on defining the executive and corporate responsibilities of publicly listed companies, especially when it comes to controlling and monitoring any type of external activity by adversaries. A very interesting example of the new agreement reached in March this year refers to Home Depot’s large-scale data leak in 2014.

Based on over 20 years of experience in cybersecurity, and having followed many of the developments in the world of security with varying degrees of success, we see very clearly that this change will soon impact our way of thinking, acting and dealing with our threats.

CounterCraft

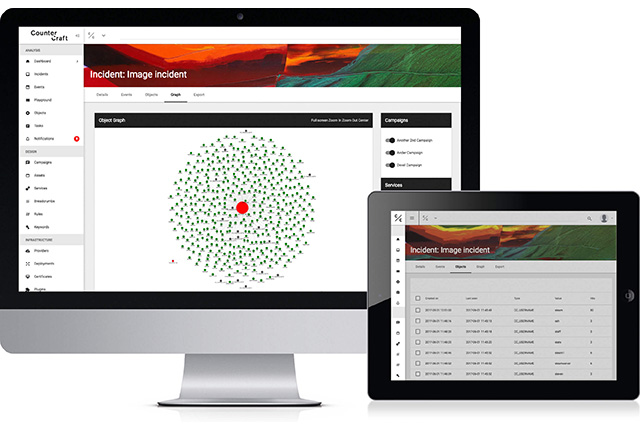

That one step further is a firm belief in CounterCraft. We help the blue defensive teams design, deploy, monitor and interact with their adversaries. And all of it using the CounterCraft project, which automates the deployment of believable deception scenarios, both internally and externally.

The idea of using deception techniques is not new. It has been used since the beginning of humanity, and in terms of technology, was first documented in the brilliant book ‘The Cuckoo’s Egg’, by Clifford Stoll. Some companies and governments have periodically used these techniques since that time, but they have always been difficult to deploy, monitor or automate. Advances in technology, coupled with complex organisations and sophisticated adversaries, have made it possible to reuse deception techniques – with zero false positives and an immediate return on investment.

Most cybersecurity products either try to better analyse existing data or create new relevant data. In the case of CounterCraft, we create new relevant data with no false positives. We generate our own intelligence based on real interactions with our adversaries.

When we use deception techniques, not only are we interested in detection but also in:

- Detecting the early stages of an attack.

- Identifying adversaries. We’re not talking about attribution – attributing an attack is very complicated – but rather creating a profile of the attacker.

- Gathering as much information as possible about adversaries: tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs).

- Manipulating the surrounding environment and context.

These deception scenarios consist of a variety of machines, documents, web applications, mobile applications, routers, identities, credentials, wireless access points, etc., deployed both internally and externally. They are fake elements that look and behave like real ones, and are situated in the same environment. Since they’re fake, there’s no need to install agents in the production elements, which renders deployment very agile and does not impact production systems.

To draw adversaries to our scenarios, we use the ‘breadcrumb’ concept, leaving pieces of information in different locations to attract attackers. The breadcrumbs can be deployed internally in all an organisation’s equipment, databases and any other place inside or outside the organisation.

Generally speaking, many of these scenarios coexist, are very dynamic by nature, and have varying objectives, including:

- Protecting management

- Spear phishing attacks

- Information leaks

- Internal or external compromises

- Sideways movements

- Protection of wireless networks in critical locations.

- Specialized attacks: SWIFT, ATM machines, SCADA, PLCs, etc.

Committed to the international market

From the very beginning, CounterCraft set its sights on the international market. Our experience in other international enterprises has showed us that, much like companies in Israel and the United States, we must place our bets on being global leaders and pioneers in technology.

If we want to compete for leadership in an emerging market like deception techniques and technologies (already dubbed by Gartner as DDP – Distributed Deception Platforms), we must do away with taboos and traditional schemes. This is the only way we can be as successful as our competitors, all of which are cut from the same cloth: Israeli companies well entrenched in the United States.

Even as a start-up, we’ve already exhibited in the industry’s leading international trade fairs – RSA Conference San Francisco, Infosecurity London, and RSA Conference Abu Dhabi – and have worked from day one with prominent market analysts.

An international technology company can indeed be created in Spain today. We are seeing a growing number of Spanish companies in the cybersecurity industry fighting side-by-side against stiff international competition to carve out a niche in the global market.

And the efforts are paying off. We are very fortunate to have a healthy number of clients, in Spain and abroad, who see the need to take one step further. Our participation in the first accelerator programme created by GCHQ, the British intelligence and security organisation, was a giant step for CounterCraft, both in terms of entering the UK market and in improving the technical aspects of the product.

The differences between organisation when it comes to making this strategic change do not differ greatly from one country to another: we’ve seen a similar vision among companies in Europe, the United States and even some countries in Asia. The main difference, if we focus on sectors, is more obvious. It’s not unusual to find the financial sector in the lead in matters of cybersecurity awareness and preparedness. However, sectors including the military, government, energy and telecommunications are not far behind.

Continuous learning

This new way of confronting cyber threats is challenging. It means venturing into a largely unexplored territory, and is bound to evolve at breakneck speed in the coming months.

It’s difficult to change our immediate reaction to a security incident. The typical reaction is to block everything we identify as malicious. But what if it were more beneficial to manipulate and monitor our adversaries instead of blocking them?

There are still a lot of unknowns and the only way to solve them is from experience. Questions like ‘What fake information can I provide?’ or ‘What’s the next step now that our scenario has been compromised?’ Or if you’ve gathered conclusive information about an adversary from a foreign country, ‘What can we do now?’. The questions are difficult to provide answers for today, but we’ll have to work them out in the very near future.

The most important question that we need to answer today is: When do we want to start managing our adversaries and all the situations that will result from being more proactive? The answer, dear reader, is in your hands.

Author: David Barroso, CEO and Founder of CounterCraft